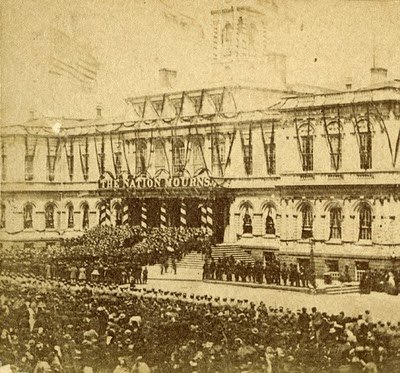

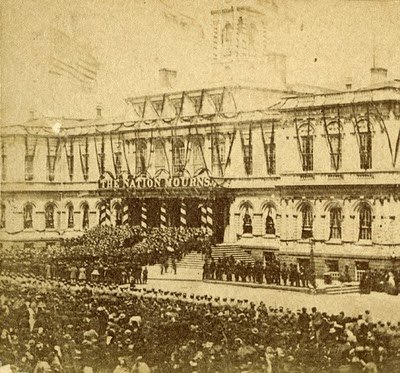

(Author’s Note: For the past twelve days, I’ve been publishing a series of posts marking the 145th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. His death on April 15, 1865 plunged the nation, already stricken by the horrors of a war which had cost 600,000 lives, into a new spasm of grief as it mourned the president. The national spectacle which followed as thirteen cities hosted funerals for Lincoln has never been repeated. New York City had its chance to pay its respects to Abraham Lincoln 145 years ago today, on April 25, 1865.)

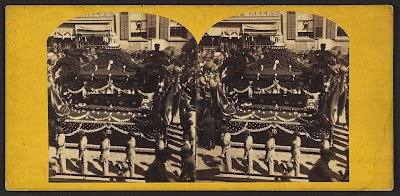

It was in the rotunda of New York City Hall where the only known photo of Abraham Lincoln in death was taken. The photo, which is shown at the beginning of this post, shows Lincoln in the casket, while an admiral and general pose at opposite ends. It was taken by a New York photographer, who stood in a high section of the balcony at the opposite end of the rotunda. When Secretary of War Edwin Stanton heard that such a photo had been taken, he was furious and ordered all the plates of it destroyed. Pleas from New York to preserve the scene for posterity went unheeded and eventually the plates were destroyed. However, a single print was sent to the Secretary to show him how dignified the photo was. Stanton fortunately kept the print in his papers, where it was discovered by his son twenty-two years later. Ultimately, the print found its way to the Illinois State Historical Library, where a young Lincoln enthusiast discovered the photo in 1952.

Lincoln’s remains were displayed at New York City Hall for the remainder of the day and night on April 24. The coffin was placed at an angle, so people approaching on the staircase leading to the rotunda could see his face all the way up. However, the approach to the staircase was so narrow and dark that just 80 people per minute could file past the remains while a crowd of at least 500,000 waited outside under brilliantly sunny skies. It was a poorly conceived decision by the city fathers to host the president’s remains in such cramped quarters. Countless thousands of mourners never got their chance to enter the building by the time it closed for the night.

The funeral procession began on schedule at 2:00 p.m. It was led by mounted police, who were followed by high ranking generals and their staffs. The hearse was next, followed by approximately 11,000(!) soldiers marching to the sounds of muffled drumbeats. More representatives of foreign nations rode in the procession, their bright colors offering a marked contrast to the sea of black throughout the city. Union and trade groups, Masons, singing societies, various ethnic organizations and groups of children marched along. In addition to the 11,000 soldiers taking part, it’s estimated that at least 75,000 other people marched in the procession. Indeed, it was so massive that the parade of mourners took nearly four hours to cross a particular point from beginning to end. There were 100 bands playing, cannons fired, and church bells throughout the city tolled while the procession seemingly lasted an eternity.

Among the throngs of people watching the funeral procession that April day in 1865 was a young boy only six years of age. He watched from his grandparents’ home located close to Union Square. That child was Theodore Roosevelt, who in 1901 would become the 26th President of the United States upon the assassination of another president, William McKinley.

Perhaps the most pathetic group of marchers in the procession were 300 African-Americans who had to practically fight to be included in the wave of white faces. At first orders had come down from the mayor and city council that NO black people were to be permitted to take part in the procession, which would be almost unbelievable were it not sadly true. Originally, a contingent of 5,000 African-Americans had plan to take part until the orders from city hall came down. There was outrage among the population, for if Lincoln had worked so hard to achieve their freedom, they should surely be permitted to honor the man who freed them. Finally, a telegraph from Secretary of War Stanton arrived, ordering New York to allow the black mourners to march. But by then it was too late to organize such large numbers. In the end, there were only those 300 African-American people, and they had thoughtlessly been placed at the very tail of the procession.

Finally at around 4:00 p.m. that day of April 25, 1865, Abraham Lincoln left New York for the final time, even though his funeral procession would take nearly two more hours to complete. The next destination was the state capital of Albany, which waited to hold its own funeral for the 16th president. That will be the subject of my next post.