I was recently asked to review a new book which claims that mental illness helped some of the most powerful moral and political leaders in history to achieve greatness.

I was recently asked to review a new book which claims that mental illness helped some of the most powerful moral and political leaders in history to achieve greatness.

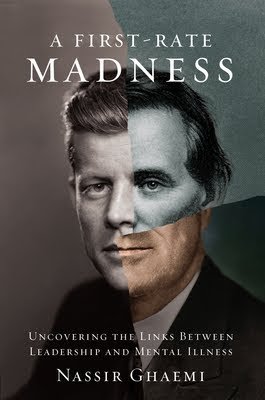

The book is titled “A First-Rate Madness” and it’s author is an esteemed psychiatrist, Nassir Ghaemi. Dr. Ghaemi is professor of psychiatry at Tufts University School of Medicine, graduate of Harvard Medical School, and also holds an undergraduate degree in history.

“A First-Rate Madness” describes the mental afflictions which affected such important leaders as Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, Franklin Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Abraham Lincoln. Each leader is discussed in a chapter or two. Since the focus of this blog is Abraham Lincoln, this review will focus on the chapter about him.

Dr. Ghaemi discusses Lincoln’s well-known bouts of depression in his chapter “Both Read The Same Bible”, text taken from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. He writes about Lincoln’s apparently serious despair in 1835 after the death of his supposed girlfriend Anne Rutledge. Lincoln was supposedly watched over by close friends at New Salem, who feared for his life. Another episode when Lincoln was struck by deep depression was in 1841 after his broken engagement to Mary Todd, when he wrote: “I am now the most miserable man living.”

As I wrote, these episodes of Lincoln’s depressive episodes are well-known to people who have read even casually about him. But Dr. Ghaemi takes these known episodes and stretches them to make what to me seems to be an unsubstantiated claim: that Lincoln “suffered from severe depression, probably a version of manic-depressive illness” and that “Most of the time, Lincoln was a highly depressed, even suicidal man.” Well.

Dr. Ghaemi’s chapter on Lincoln uses as its main source the 2005 book “Lincoln’s Melancholy” by Joshua Wolf Shenk. That book caused somewhat of a controversy among Lincoln scholars and historians about its claim of Lincoln’s “serious depression.” Harold Holzer for one, doesn’t accept the theory that Lincoln was nearly incapacitated by his “hypochondria” as Lincoln called it. Otherwise, how could Lincoln have pulled himself together over the course of four years in leading the country in the Civil War, especially after the death of his favorite child, Willie, in 1862? Personally, I agree with Mr. Holzer; Lincoln couldn’t have been so depressed as to be suicidal “most of the time” or else he couldn’t have led the country, let alone so brilliantly led it.

Dr. Ghaemi then goes on to try to show how Lincoln’s depressive episodes made him more receptive to political realism. He gives more well-known examples: Lincoln’s early opposition to abolition; his support for colonization of freed slaves; his eventual acceptance of ending slavery; and his magnificent Second Inaugural Address, where he refused to “gloat” over victory.

I would have believed more about Dr. Ghaemi’s chapter about Abraham Lincoln had he used more than one significant source for it, especially a controversial book full of disputed historical facts and assumptions. He also doesn’t make a very convincing connection (for me, at least) between Lincoln’s “constant” depression and brilliant leadership.

I am neither psychiatrist nor medical doctor of any kind. But I do know a fair amount about Abraham Lincoln. And I know enough to understand that Dr. Ghaemi’s thesis about Lincoln’s “madness” turning him into a great leader seems to be weak, at best. It forces me to wonder about the other claims for other leaders in the rest of the book, which I have admittedly yet to read.

In summation, “A First Rate Madness” has an interesting premise, but ultimately, the premise cannot be proven, at least about our nation’s greatest president. Spend your time and money on other (and better) books if you wish to read more about Lincoln’s legacy and life.