British soldiers are marched to the rear after surrendering to the Germans at Dunkirk. Members of the rear guard delayed the German advance for a week, permitting the evacuation of more than 330,000 Allied troops.

This week marks the 75th anniversary of the Dunkirk evacuation, the “miracle of the little ships” that plucked thousands of British and Allied soldiers from the French port and its adjacent beaches, allowing them to escape, and fight again another day.

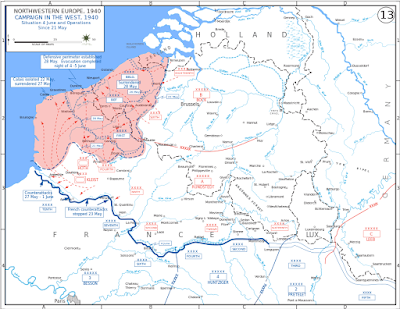

Dunkirk remains one of the early turning points of the Second World War. More than 400,000 Allied troops faced certain annihilation on the beaches of northern France, following the German blitzkrieg through the low countries and the Ardennes, by-passing the defenses of the famous Maginot Line. As Nazi armored columns rushed ahead, elements of the French Army began to collapse; what could have been an orderly retreat became a full rout, as the allies fell back towards the channel ports, with the Germans closing in to administer the coup de grace.

Instead, more than 300,000 members of the British Expeditionary Force and the French Army were rescued from the area around Dunkirk, the small port that remained in Allied hands, and still able to support an evacuation. The British, like all armies in 1940, were poorly prepared for amphibious warfare, and lacked sufficient numbers of landing craft to deliver men and supplies onto a beach, or (in the case of Dunkirk) transport them to safety. Planners initially believed that a small number of troops (perhaps 45,000) could be rescued through the port; the decision to mobilize small, shallow-draft vehicles allowed evacuation from the beaches as well.

That’s one reason Dunkirk is so often associated with the flotilla of fishing boats, pleasure craft, coastal steamers and lifeboats that were requisitioned by the British Admiralty, and pressed into service during the operation. Some of the vessels were used to ferry hundreds of soldiers back to the U.K.; others had the dangerous job of transporting evacuees from the beach to larger ships off-shore. The smallest craft was a 15-foot fishing vessel named Tamzine that is now preserved at the Imperial War Museum. Virtually all were skippered by Royal Navy personnel or experienced merchant seamen; only a handful of civilian boat owners actually sailed their vessels to France and back, a myth popularized in the film Mrs. Miniver and war-time propaganda.

But Dunkirk was more than a miracle of little boats, braving a perilous journey to France and back. The seeds of the successful rescue mission were sown when the BEF Commander, Lord Gott, decided not to support a French counterattack to the south, aimed at cutting off the panzer columns of General Heinz Guderian, who had raced across France to the sea. Gott understood the French had missed the window for a launching a successful offensive; instead, he ordered the BEF to begin moving back towards Dunkirk on 25 May, realizing it was the only hope for saving the core of Britain’s regular Army.

The Germans would also play a critical role in the ultimate success of Dunkirk. Guderian was chastised for pressing ahead to the coast by his superiors, who believed it left their flanks badly exposed. There was also concern about mounting losses of tanks and other armored vehicles among panzer units. When Hitler visited the headquarters of General Gerd von Rundstedt, the commander of Army Group A, which led the German push through the Ardennes and across France, he suggested halting the armored forces west of Dunkirk, leaving it up to the infantry–and the Luftwaffe–to destroy what was left of the BEF.

Hitler agreed, and it proved to be the decisive point in the campaign, though it’s not completely clear why Hitler went along with the plan. Certainly, there was the issue of terrain (the Germans believed marshy ground around Dunkirk was unsuited for tanks); the need for panzer units to rest and resupply after the dash across France, and worries about renewed Allied counter-attacks. Just three days earlier, on 21 May, the BEF mounted a strong push near the city of Arras in northeastern France, destroying dozens of German tanks and inflicting over 400 casualties before they were forced to retreat.

Dunkirk campaign map, depicting the steadily shrinking Allied perimeter in late May and early June 1940 (United States Military Academy via Wikipedia)

With Arras fresh in his mind–and other tactical considerations influencing his thinking, von Runstedt grew hesitant. He issued a Halt Order on 24 May and it was validated by Hitler several hours later. Panzer units were directed not to advance past the Lys Canal; the job of finishing off the BEF would be left up to the infantry and the Luftwaffe, at least initially. After the war, von Runstedt and other German generals tried to blame the halt directive on Hitler but it is clear the order began with the military and der Furher merely endorsed their plan. Incredibly, at the time the halt order was issued, lead panzer elements were actually closer to Dunkirk than most of the BEF troops who were later evacuated (emphasis ours). In a later diary entry, even Hitler admitted that thousands of British and French troops escaped “under our noses.”

The successful evacuation needed two more elements: air cover, and perhaps most importantly, troops who would fight the rear guard action, holding off the Germans long enough for most of their comrades to escape. Air support had been a thorny issue in the weeks before Dunkirk; the RAF had been criticized for withholding Spitfire squadrons from the fight during the Battle of France. Fighter Command’s CIC, Air Marshal Hugh “Stuffy” Dowding calculated (correctly) that his best fighter units would be needed to defend England in the months ahead. But as the evacuation got underway, Dowding threw all available resources into the fray; soldiers trapped on the beaches complained they saw more German aircraft than RAF fighters, but the British provided enough air cover to allow the operation to succeed. Enemy dive bombers and other aircraft managed to sink scores of ships–including several Royal Navy destroyers–but the operation, nicknamed “Dynamo”–continued.

But the real heroes of Dunkirk were the British and French soldiers who took up positions to protect the port and the thousands of troops awaiting evacuation. Theirs was a thankless task; running short on food, ammunition and medical supplies, they were supposed to hold off the advancing Germans as long as possible, facing almost certain death or capture at the end of their mission. General Alan Brooke was ordered to mount a holding action with the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 50th divisions along the Ypres-Comines Canal while the rest of the BEF retired towards Dunkirk; General Ronald Adam, the III Corps Commander, was put in charge of establishing perimeter defenses around the port.

Between 27 May and 1 June, the men of the BEF rear guard mounted a determined defense, slowing the German advance (which resumed on the 26th). Their valiant stand allowed the bulk of British forces to make their way to Dunkirk, where they were evacuated by the Royal Navy. While many historical accounts focus on the small boats ferrying soldiers from the beaches, most of the troops departed via the sea walls (or “moles”) that protected the harbor, since Dunkirk’s damaged docks could no longer handle ships. Under the direction of Royal Navy Captain (later Vice Admiral) Bill Tennant, the evacuation quickly gathered steam; at its peak, on 31 May, just over 68,000 soldiers were rescued from the sea walls and the beaches on a single day.

Further inland, between 30-40,000 British troops, along with a larger French contingent, fought desperately to stem the German tide, buying more time for their comrades to escape. While a few members of the rear guard were able to reach Dunkirk (and make their way onto one of the final evacuation ships), most were forced to surrender. Near the village of Le Paradis, in the Pas-de-Calais region, member of the 3rd SS Division Totenkopf massacred 97 British POWs from the Royal Norfolk Regiment. Most of the BEF troops who surrendered were transported to detention camps in Poland where they would remain for the next four years. Unfortunately, their suffering was not over; in the winter of 1944-45, with Russian forces advancing from the east, thousands of British and French POWs were forced-marched to other prison camps in Germany. Hundreds more died from disease and exhaustion in the bitter cold.

To this day, historical accounts of Dunkirk tend to focus on the remarkable evacuation, which saved so many Allied troops who were instrumental in later victories in North Africa, the Far East, and in the European campaigns that finally liberated the continent. Yet, the “miracle” of Dunkirk came at a high price; hundreds of troops and sailors died at sea, when their ships were sunk by the Luftwaffe or the German Navy; the RAF lost more than 100 aircraft (and dozens of badly-needed fighter pilots) during engagements over France or the English Channel. But the greatest sacrifice was paid by the men who held the line so that other troops would live and carry the fight in future battles. Their orders were simple and to the point:

‘You will hold your present position at all costs to the last man and last round. This is essential in order that a vitally important operation can take place.’

History records that the troops of the Dunkirk rear guard did just that, setting the stage for the miraculous evacuation that was playing out just a few miles away.