It was 150 years ago today that Abraham Lincoln was elected as the 16th President Of The United States on November 6, 1860. The Presidential election of 1860 was contentious to be sure, but it remains the most momentous vote in our nation’s history, because it began the chain of events which led to the U.S. Civil War.

It was 150 years ago today that Abraham Lincoln was elected as the 16th President Of The United States on November 6, 1860. The Presidential election of 1860 was contentious to be sure, but it remains the most momentous vote in our nation’s history, because it began the chain of events which led to the U.S. Civil War.

The major issue facing Americans as they voted that day in 1860 was, of course, slavery. For decades the slavery debate had been simmering in the country, but it had boiled over in the preceding few years. In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its infamous Dred Scott decision, in which the court ruled that Congress had no right to interfere with slavery anywhere in the states or U.S. territories, indeed that slaves themselves were technically not persons as recognized by the law. Then in 1859, John Brown’s raid on the Federal Arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) where he hoped to cause a slave insurrection, further fanned the flames of the slavery argument roiling the United States.

As the election of 1860 approached, the major political parties held their conventions. The Democrats met in Charleston, S.C. on April 23 and almost immediately split into two parties, the Northern and Southern Democratic parties. The issue even within the party was slavery. The Northern Democratic delegates wanted the notion of “Popular Sovereignty” in which people in a U.S. territory (such as Kansas and Nebraska) would hold a vote to determine if slavery would be permitted or not. The very idea of the people deciding was anathema to Democratic delegates from the Southern states, and those delegates walked out of the convention. They wanted the Federal government to protect slavery where it already existed and to guarantee the right for its spread into the territories, no matter if the majority of the people wanted it or not.

With the collapse of the Democratic convention in Charleston, the Northern delegates met again in June at Baltimore, Maryland. There they nominated U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, who had been Lincoln’s chief political rival for many years. Lincoln and Douglas had of course held a series of debates (7 in all) across Illinois two years earlier in 1858 as they debated the slavery issue during the U.S. Senate campaign. Douglas went on to win election to the Senate, but the debates thrust Lincoln into the national spotlight. The photo below is of Senator Douglas. Nicknamed the “Little Giant” (he was just 5’4″ tall), he was a masterful politician and an early suitor of Mary Todd Lincoln. The Southern Democratic delegates met at the same time also in Baltimore and nominated as their candidate John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, who had been James Buchanan’s vice-president. Breckinridge was the youngest-ever U.S. vice-president, serving at just age 36. He strongly supported the demands of the Southern Democrats for the protection of slavery throughout the U.S. territories. The photo below shows Breckinridge.

The Southern Democratic delegates met at the same time also in Baltimore and nominated as their candidate John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, who had been James Buchanan’s vice-president. Breckinridge was the youngest-ever U.S. vice-president, serving at just age 36. He strongly supported the demands of the Southern Democrats for the protection of slavery throughout the U.S. territories. The photo below shows Breckinridge. Another political party appeared on the scene in 1860. Calling itself the Constitutional Union Party, it’s sole goal was to preserve the Union. Baltimore was a popular convention city in late spring 1860, and the delegates from this party met there as well. The Constitutional Unionists did their best to appeal to both sides of the political debate. It nominated a former Speak of The House, John Bell of Tennessee. It’s only platform point was to adhere to the Constitution. Below is a photo of John Bell.

Another political party appeared on the scene in 1860. Calling itself the Constitutional Union Party, it’s sole goal was to preserve the Union. Baltimore was a popular convention city in late spring 1860, and the delegates from this party met there as well. The Constitutional Unionists did their best to appeal to both sides of the political debate. It nominated a former Speak of The House, John Bell of Tennessee. It’s only platform point was to adhere to the Constitution. Below is a photo of John Bell. The Republican Party met in Chicago in May 1860, in a huge structure called “The Wigwam.” Lincoln was not the front-runner or favorite to win the nomination. That designation fell on William H. Seward of New York, a former Senator and Governor of that state. Lincoln’s handlers or “men” were brilliant behind the scenes and out-manoeuvred Seward’s. For example, Lincoln’s supporters had counterfeit admission tickets printed for entry into the Wigwam and packed the building with “Lincoln men” when Seward’s were out attending other functions. By the time the Seward supporters returned to the building, they found their seats already occupied. The first ballot of the convention had Seward in the lead, but without enough to reach a majority. Finally with much effort and a lot of “horse trading” Lincoln’s supporters enabled him to clinch the nomination on the third ballot. The photo at the beginning of this article shows Lincoln as he appeared in summer 1860, just after the nomination.

The Republican Party met in Chicago in May 1860, in a huge structure called “The Wigwam.” Lincoln was not the front-runner or favorite to win the nomination. That designation fell on William H. Seward of New York, a former Senator and Governor of that state. Lincoln’s handlers or “men” were brilliant behind the scenes and out-manoeuvred Seward’s. For example, Lincoln’s supporters had counterfeit admission tickets printed for entry into the Wigwam and packed the building with “Lincoln men” when Seward’s were out attending other functions. By the time the Seward supporters returned to the building, they found their seats already occupied. The first ballot of the convention had Seward in the lead, but without enough to reach a majority. Finally with much effort and a lot of “horse trading” Lincoln’s supporters enabled him to clinch the nomination on the third ballot. The photo at the beginning of this article shows Lincoln as he appeared in summer 1860, just after the nomination.

According to most historians, the election of 1860 ended up becoming almost two contests: Lincoln vs. Douglas in the Northern states, and Breckinridge vs. Bell in the Southern states. In fact, Abraham Lincoln’s name was not even placed on ballots in nine states in the South.

Douglas broke with tradition and actively campaigned around the country (until 1860, candidates for President did not campaign on their own behalf), wearing himself out so much that he would die on June 3, 1861. He toured the Northern states to be sure, but he also traveled throughout the South. There he asked the Southerners to accept any outcome of the election, even if Lincoln would be elected. Of course, his pleas went unheeded as a state of extreme agitation existed in the South, increased by harsh attacks by the Southern newspapers on Lincoln, even months before the election.

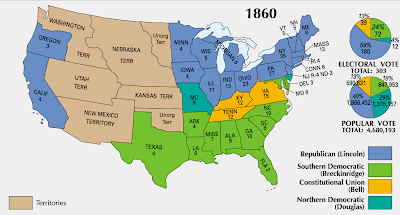

The results of the 1860 presidential election revealed that for the first time in U.S. history, the country had divided along sectional lines. Lincoln won the Northern states while Breckinridge won most of the Southern states. Bell carried Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Poor Stephen Douglas won just the state of Missouri and 3 electoral votes in New Jersey. It comes as a surprise sometimes to people when they first learn that Lincoln won just 39.9% of the popular vote in the 1860 election. His three opponents combined to earn approximately 1 million more votes than he did!

Of course, as we remember from the 2000 presidential election, a president doesn’t win based on the popular vote. In the 1860 election, Lincoln was the clear winner in the Electoral College, outdistancing those electoral votes earned by his three opponents combined. Below is an excellent image which shows the election map of 1860. Lincoln states are in blue; Breckinridge states are green; the states Bell won are yellow; and the states Douglas won are in aqua.

It’s said that when Abraham Lincoln discovered that he had been elected the 16th President Of The United States on November 6, 1860, his face suddenly showed a heavy burden and concern, almost as if he had the weight of the world on his shoulders. He walked slowly back to his home, gently awakened his wife Mary, and simply said “Mother, we are elected.”

Within weeks of Lincoln’s election, the firebrands in the South began agitating for secession from the Union. Lincoln himself was nearly silent, not giving any speeches to try to calm the tempers which were running rampant throughout the country. Instead he preferred working behind the scenes in numerous letters to friends and supporters throughout the country.

Unfortunately, Lincoln’s election 150 years ago today became the catalyst for the greatest war ever fought by the United States of America. In a sense, today also marks the sesquicentennial of the beginnings of the Civil War era.

Over the next few months, indeed, four and one-half years, won’t you follow along with The Abraham Lincoln Blog as we remember the important events and anniversaries of Mr. Lincoln and the Civil War? There are countless fascinating facts and stories to tell. I would be honored if you joined me for the journey.