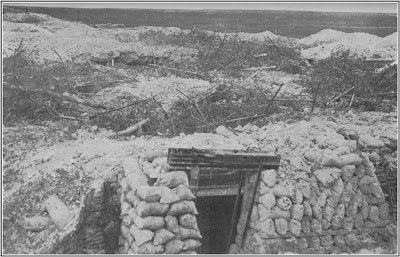

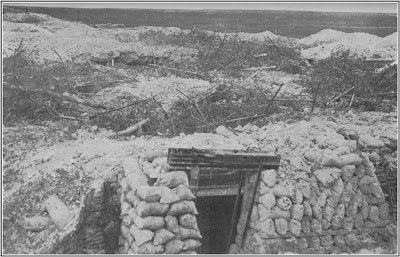

Dug-outs and barbed wire in La Boisselle. Usna-Tara Hill, with English Support Lines in Background. At Extreme Left is the Albert-Bapaume Road.

“The defences of the enemy front line varied a little in degree, but hardly at all in kind, throughout the battlefield. The enemy wire was always deep, thick, and securely staked with iron supports, which were either crossed like the letter X, or upright, with loops to take the wire and shaped at one end like corkscrews so as to screw into the ground. The wire stood on these supports on a thick web, about four feet high and from thirty to forty feet across. The wire used was generally as thick as sailor’s marline stuff, or two twisted rope-yarns. It contained, as a rule, some sixteen barbs to the foot. The wire used in front of our lines was generally galvanized, and remained grey after months of exposure. The enemy wire, not being galvanized, rusted to a black colour, and shows up black at a great distance. In places this web or barrier was supplemented with trip-wire, or wire placed just above the ground, so that the artillery observing officers might not see it and so not cause it to be destroyed. This trip-wire was as difficult to cross as the wire of the entanglements. In one place (near the Y Ravine at Beaumont Hamel) this trip-wire was used with thin iron spikes a yard long of the kind known as calthrops. The spikes were so placed in the ground that about one foot of spike projected. The scheme was that our men should catch their feet in the trip-wire, fall on the spikes, and be transfixed.

In places, in front of the front line in the midst of his wire, sometimes even in front of the wire, the enemy had carefully hidden snipers and machine-gun posts. Sometimes these outside posts were connected with his front-line trench by tunnels, sometimes they were simply shell-holes, slightly altered with a spade to take the snipers and the gunners. These outside snipers had some success in the early parts of the battle. They caused losses among our men by firing in the midst of them and by shooting them in the backs after they had passed. Usually the posts were small oblong pans in the mud, in which the men lay. Sometimes they were deep narrow graves in which the men stood to fire through a funnel in the earth. Here and there, where the ground was favourable, especially when there was some little knop, hillock, or bulge of ground just outside their line, as near Gommecourt Park and close to the Sunken Road at Beaumont Hamel, he placed several such posts together. Outside Gommecourt, a slight lynchet near the enemy line was prepared for at least a dozen such posts invisible from any part of our line and not easily to be picked out by photograph, and so placed as to sweep at least a mile of No Man’s Land.

When these places had been passed, and the enemy wire, more or less cut by our shrapnel, had been crossed, our men had to attack the enemy fire trenches of the first line. These, like the other defences, varied in degree, but not in kind. They were, in the main, deep, solid trenches, dug with short bays or zigzags in the pattern of the Greek Key or badger’s earth. They were seldom less than eight feet and sometimes as much as twelve feet deep. Their sides were revetted, or held from collapsing, by strong wickerwork. They had good, comfortable standing slabs or banquettes on which the men could stand to fire. As a rule, the parapets were not built up with sandbags as ours were.

In some parts of the line, the front trenches were strengthened at intervals of about fifty yards by tiny forts or fortlets made of concrete and so built into the parapet that they could not be seen from without, even five yards away. These fortlets were pierced with a foot-long slip for the muzzle of a machine gun, and were just big enough to hold the gun and one gunner.

In the forward wall of the trenches were the openings of the shafts which led to the front-line dugouts. The shafts are all of the same pattern. They have open mouths about four feet high, and slant down into the earth for about twenty feet at an angle of forty-five degrees. At the bottom of the stairs which led down are the living rooms and barracks which communicate with each other so that if a shaft collapse the men below may still escape by another. The shafts and living rooms are strongly propped and panelled with wood, and this has led to the destruction of most of the few which survived our bombardment. While they were needed as billets our men lived in them. Then the wood was removed, and the dugout and shaft collapsed. “